The Abbasid Caliphate was an Arabic dynasty that ruled over much of the Muslim world for over 500 years. It rose from bloody beginnings to become the center of the Muslim world during the Islamic Golden Age under the legendary Harun al-Rashid. It was perhaps Islamic history’s grandest and most powerful Empire, but it ultimately fell like all Empires that came before and after. The Abbasid’s story is one of ascendancy, cultural brilliance and eventual unraveling. An unraveling that took centuries but ended with a massive Mongol invasion that shook the Islamic world to its core. This is that story.

The Abbasid Caliphate, the Golden Age of Islam and the First Caliphates

When it comes to Islamic history people often use the words “empire” and “caliphate” interchangeably. While they are similar, the key difference between the two is that while an empire is a more general term, a caliphate is a form of Islamic governance led by a caliph, considered the political and religious successor to Prophet Muhammad.

The idea of a caliphate was first conceived in 632 AD after the death of the Prophet Muhammad on June 8, 632 AD. The word caliph comes from the Arabic word khalifah, which means “successor” or “representative.” The caliphs were expected to uphold and implement Islamic principles, lead the community, and serve as both political and religious authorities.

According to Sunni Muslims, the original four caliphs were Abu Bakr, Umar ibn al-Khattab, Uthman ibn Affan and Ali ibn Abi Talib who all belonged to the Rashidun Caliphate. Shia Muslims disagree, however, and only count Ali ibn Abi Talib as a true caliph, regarding the first three as usurpers since only Ali was related to the prophet directly (he was his cousin and son-in-law).

The Rashidun Caliphate didn’t last long and ended with Ali’s assassination in 661 AD when he was attacked with a poisoned sword while praying. Following the Rashidun Caliphate came the Umayyad Dynasty, the Arab world’s first absolute monarchy.

The Umayyads reigned for around 90 years, from 661 to 750 AD. Muawiyah I became the first Umayyad caliph in 661 AD, and the capital of the caliphate was moved from Medina to Damascus. The Umayyads ruled over a vast empire that stretched from Spain in the west to the Indian subcontinent in the east.

Their rule was defined by a mixture of excellent administration and brute force. Over time the dynasty became weakened by internal turmoil. Arab and non-Arab factions like the Shias and Persians became increasingly alienated and the royal family’s inner circle began to fracture. When the last Umayyad king, Marwan II, came to power in 747 AD he was facing an open rebellion.

The remains of Qasr Amra in Jordan, a desert castle which was once home to Umayyad princes before their overthrow by the Abbasids. (Radek Sturgolewski / Adobe Stock)

The Abbasid Revolution

This rebellion was led by a mysterious figure simply called Abu Muslim. Little is known about him except for the fact that it was he who ended Umayyad rule and brought the Abbasids to power through scheming and political maneuvering even though he wasn’t an Abbasid himself.

The Abbasids took their name from Abbas ibn Abd al-Muttalib, their ancestor and one of Muhammad’s youngest uncles. They used this connection to claim that the throne was their holy right or their Ahl al-Bayt. Led by Abu Muslim the Abbasid campaign started as an underground movement, but by 750 AD a full-on revolution was underway.

Caliph Marwan, desperate to put the rebellion down, ordered that the Abbasid patriarch, Ibrahim, be captured and killed. This only made him a martyr, and when his brother, Abu Abbas, replaced him he swore revenge against the current caliph.

Abbas led the majority of the Abbasid forces against Marwan’s remaining army near the Greater Zab River shortly after his brother’s death. It was a bloody victory for the Abbasid forces and Marwan and his men fled in panic. Marwan fled to Egypt to seek help but was quickly found and killed. Abu Abbas then became the first Abbasid Caliph and became Abu Abbas as-Saffah – “the bloodthirsty.’

The Early Days of Abbasid Rule

His first act as caliph was to take his army and march them to Central Asia where the Chinese Tang Dynasty had been capitalizing on all the unrest to expand into Muslim lands. This expansion was put to an end at the battles of Talas in 751 AD with the Muslim forces crushing the Tang troops.

Rather than push further into Tang territory, Abu Abbas instead decided to make peace. Instead of focusing on expanding his newly won empire, he decided it was best to secure the borders and build up from the inside. This was an approach followed for much of the Abbasid’s 500-year rule; stability over expansion.

This process began with As-Saffah wiping out any Umayyad he could find to prevent any potential uprising. All the living male members of the family were massacred, and Umayyad graves were defiled to send a message to potential supporters. This drove many of the surviving Umayyads into hiding.

But As-Saffah was as cunning as he was ruthless. He sent a dinner invitation out to the Umayyads promising an end to the bloodshed and saying he now wished only for reconciliation. Those who turned up were brutally murdered in front of As-Saffah and his officials as they gorged on the feast.

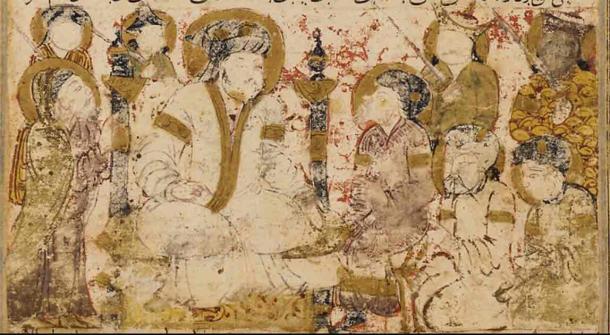

Depiction of Abu Abbas as-Saffah, the first caliph of the Abbasid Caliphate, within a 14th-century manuscript. (Public domain)

Rise of the Abbasid Caliphate

Four years after coming to power As-Saffah died and was replaced by his brother, Ja’afar, titled al-Mansur (“one who is victorious”, r. 754-775 AD). One of his first acts was to establish the first Abbasid capital (something As-Saffah had never gotten around to). This metropolis was built near the Tigris River and named Baghdad. It would soon grow into a city that made every European city look insignificant in comparison.

Al-Mansur then got to work consolidating Abbasid power against potential future threats. With the Umayyads all but wiped out he focused his ire on the descendants of Ali. He did so by tricking them into a revolt and then crushing the ensuing rebellion in 763 AD. He even went as far as murdering Abu Muslim (the man responsible for the Abbasid’s position in the first place). His mutilated body was dumped in the Tigris River, a warning to other ambitious men.

Thankfully, al-Mansur’s son, al-Mahdi, wasn’t as bloodthirsty as his father or uncle. He knew that his father’s brutal style of rule had only served to stir up sympathy for the Umayyads and so, decided to be a more benevolent ruler.

After coming to power in 775 AD he released all the Alids his father had captured and offered them reparations as compensation for the family members his father had massacred. In doing so he turned some of his most dangerous enemies into greatest allies. He showed similar generosity to the rest of his subjects and even fell in love and married a slave girl, Al-Khayzuran. He not only freed her from slavery, but he also made her his first queen.

This isn’t to say al-Mahdi was a pushover. In battle he was just as ruthless as his predecessors. He happily put down Byzantine incursions into his lands (something they’d been doing since the days of the Prophet himself and would continue to do for many years), extracting tributes from them after each defeat. One such example was in 782 AD when al-Mahdi sent his favored son to put down Empress Irene’s forces. It was an easy win, and the Byzantines were forced to beg for peace.

Sadly, al-Mahdi was betrayed in 785 AD and poisoned by one of his concubines. He was followed by his eldest son, al-Hadi, who ruled for less than a year. There’s much speculation as to what happened to this young caliph. Some believe he died from an incurable disease, but others suspect his brother, Harun, or his mother played a role in his early demise.

Building the Golden Age of the Abbasid Caliphate

The young al-Hadi was succeeded by his brother, Harun al-Rashid (despite the fact Hadi had wanted his sons to take the throne rather than his brother). Al-Rashid went on to become an almost legendary figure and by far the most famous of the Abbasid rulers. It can be difficult to separate fact and fiction when it comes to this remarkable man.

Al-Rashid wanted the Abbasid Caliphate to become a center of arts and learning and believed the Muslims should lead the world in culture. As such it was he who ordered the building of the Grand Library of Baghdad, the Bayt al Hikma (meaning “House of Wisdom”).

Al-Rashid sent envoys out into the world to collect as many Greek works as they could find. These were then translated into Arabic in his great library. By doing so he preserved works that would inspire the Renaissance centuries later.

While Harun focused on his pet project, he handed over the business of actually ruling his empire to his most trusted advisors. While this could have been a recipe for disaster, he did an excellent job in selecting the most talented and trustworthy of men. His government became a beacon of good administration, and the caliphate went from strength to strength.

In 806 AD the Byzantines once again tried to attack the Abbasid empire and their emperor, Nikephoros I, sent the caliph an insulting letter in the process. Al-Rashid was so incensed he took to the battlefield personally and the Abbasids yet again crushed the Byzantine forces. Yet more reparations were then extracted from the old nemesis.

If al-Rashid made one mistake it was when he made the western province of Ifriqya the caliphate’s first principality, controlled by Ibrahim ibn Aghlab. While this seemed like a promising idea on paper (the region had been a major pain for decades and giving it a modicum of autonomy calmed things down considerably) it later turned out to be the first step in the caliphate’s long and painful disintegration.

Harun al-Rashid receiving a delegation sent by Charlemagne at his court in Baghdad, in a painting by Julius Köckert. (Public domain)

Civil War Strikes the Abbasid Caliphate

When al-Rashid died in 809 AD his favorite son al-Amin was given the throne with the understanding that his brother, al-Ma’mun, would be given territories which he would rule over as a subject to the Caliph. Al-Rashid’s plan was that this agreement would stop the brothers from falling out over who got to be caliph. The plan didn’t work.

Two years after the great leader died, a massive civil war between the two brothers broke out. Known as the Fourth Fitna or the Great Abbasid Civil War it lasted from 811 to 819 AD although things didn’t really calm down in some areas until the 830s. It was a long, drawn-out war that eventually saw al-Amin surrender to his brother’s forces. Al-Ma’mun ruled until 833 AD. He attempted to follow in his father’s footsteps but most of his reign was spent trying to fix the damage the civil war had done to the realm.

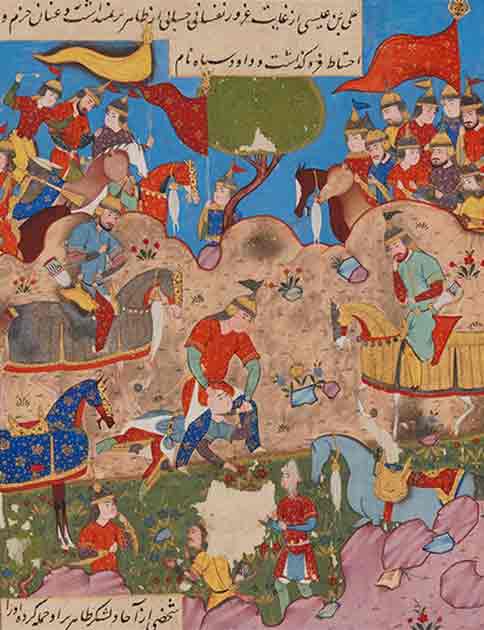

Folio from a manuscript of Nigaristan depicting the victory of Al-Ma’mun after the the Fourth Fitna. (Public domain)

The Rot Sets In

The Golden Age of Islam officially ended with the death of al-Ma’mun in 833 AD. His successors al-Mu’tasim and al-Wathik were weak and hedonistic rulers more focused on enjoying themselves than enlightening the world. While they indulged themselves, they allowed their Turkish bodyguards to secretly develop a stranglehold on the royal court.

In 847 AD al-Mutawakkil came to the throne. He was a cruel ruler, and his persecution of non-Muslim minorities has earned him the moniker “the Nero of the Arabs.” He was also a deeply unpopular ruler, leading to his assassination in 861 AD. The Turks, who had by this time fully infiltrated the court, then put his young son, al-Muntasir, on the throne as a puppet ruler.

A series of weak and ineffectual Abbasid leaders, all controlled by the Turks, inspired old enemies to rise up and announce their own caliphates. This began in 909 AD with the rise of the Fatimids and their “anti-caliphate”, who claimed to be the descendants of the prophet’s daughter. They spread across Egypt and reached as far as the cities of Mecca and Medina. Meanwhile, in 929 AD another rival caliphate, the Umayyad Emirate of Cordoba, also joined the party.

The largest threat however was the Irania-based Buyids, another Sunni dynasty, led by Ali ibn Buya. They quickly grew in size and in 945 AD succeeded in capturing Baghdad. By this time, the Abbasid rulers were already puppets, so the only real change was who was pulling the strings behind the scenes.

The Buyids controlled Baghdad until 1055 AD when the Seljuk Turks coming from Central Asia stormed the city and expelled them. Throughout this period of decline, the Abbasid Caliphate continued to disintegrate as regions slowly slipped out of its grasp, either taken by rival powers or claiming independence.

The Crusades and a Brief Resurgence for the Abbasid Caliphate

By the time the Europeans rode into the Holy Land in 1096 AD, the Abbasid Caliphate was a shadow of its former self. Surprisingly, the Crusaders did the Abbasid caliphs a massive favor and the Crusades led to a brief resurgence for the ailing caliphate.

The Seljuks soon realized they were no match for the Crusaders and bowed out of the war while the Abbasids simply watched while their Muslim brothers, led by Saladin, defeated the Crusaders. The Abbasid caliphs saw all the commotion as an opportunity and decided to bide their time.

Caliph al-Mustarshid and then al-Muktafi raised personal armies with the hopes of finally driving out the weakened Seljuks and taking back control of their caliphate. When the Seljuks realized what was going on they retaliated, leading to them attacking Baghdad in 1157 AD. The attack was a complete failure and al-Muktafi’s forces drove them from the city once and for all.

The Abbasid Caliphate was back and ready to start expanding again. The caliphate began to rebuild its once-great reputation and under Al-Nasir (the last competent Abbasid caliph) expanded into Mesopotamia and Persia. For a while, at least, things looked good.

The Mongols and the Fall of the Abbasid Caliphate

Sadly, this revival was short lived, a new threat was looming from Central Asia – the Mongols. United by Genghis Khan in 1206 AD the Mongols had begun their rise to the top, spreading like wildfire. Unfortunately, the last formal Abbasid caliph, al-Must’asim, failed to take the threat seriously.

Just before a major battle against Mongol forces led by Hulagu Khan, al-Must’asim decided to disband most of his army. Exactly why remains a mystery, but it’s thought he likely underestimated his enemy and thought that he’d receive backup from the other Islamic powers (who all had their own problems).

It was a disaster. The Mongols laid siege to Baghdad in 1258 and raised the city to the ground, massacring much of its population. The caliph was murdered in spectacular fashion—rolled into a carpet and trampled by horses. All but two members of the royal family were killed—a boy who was sent to Mongolia and a princess who was made the Khan’s sex slave and forced into his harem.

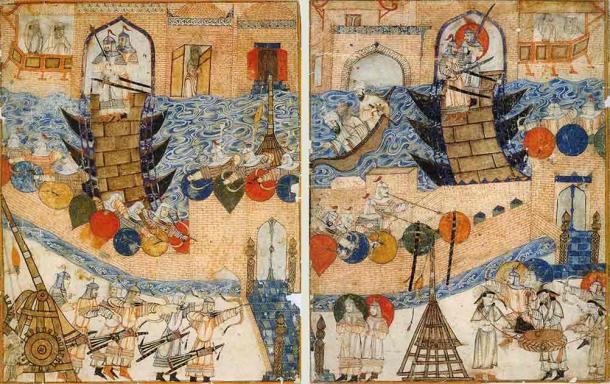

A 14th century depiction of the siege of Baghdad by the Mongols in 1258, which brought the Abbasid Caliphate to an end. (Public domain)

The End of the Abbasid Caliphate

In 1260 AD the Mamluk Sultanate put an end to the Mongol advance. They then made the surviving Abbasids shadow caliphs of Cairo. They held no actual power, however, and were overthrown by Sultan Selim I of the Ottoman Sultanate in 1517 AD. Abbasid rule, after centuries of decline, was officially over.

The Abbasid Caliphate played a pivotal role in Islamic history and its story is a complicated one. Witnessing the zenith of Islamic civilization during the Golden Age under rulers like Harun al-Rashid, it later succumbed to internal strife and external invasions. The Mongol Siege of Baghdad in 1258 marked a devastating turning point, symbolizing the end of the caliphate’s political influence.

Despite its decline, the Abbasid legacy endures in the contributions to science, philosophy, and arts, leaving an indelible mark on the cultural tapestry of the Islamic world. The rise and fall of the Abbasid Caliphate embody a complex story of power, knowledge, and resilience.

Top image: Representative image of a soldier from the Abbasid Caliphate. Source: Harry / Adobe Stock