In September 1945, shortly before his arrest by Allied soldiers, Japan’s wartime prime minister Tōjō Hideki was asked by an American reporter who he considered responsible for the war. ‘You are the victors’, replied Tōjō, ‘and you are able to name him now … But historians 500 or 1,000 years from now may judge differently.’

Here, in essence, was one of the biggest challenges that faced the International Military Tribunal for the Far East when it convened in Tokyo in April 1946: how to avoid the impression of victors’ justice? Modelled on the Nuremberg trials, then ongoing in Germany, the aim of the ‘Tokyo trials’, as they became known, was to try senior Japanese leaders for a range of crimes committed both during the Second World War and in the period leading up to it. When the trials concluded in December 1948, each of the 25 defendants was found guilty on at least one count. Seven, including Tōjō Hideki, were sentenced to death.

In obvious ways the trials did indeed represent victors’ justice. The victors set the mandate and populated the judges’ bench. Their own conduct in the war – firebombing Japanese cities and using atomic weapons on Hiroshima and Nagasaki – was exempt from consideration. And their point of view on the causes of war decided the chronology of the trials: beginning with Japanese militarism in the late 1920s, rather than – as a Japanese witness at the trial suggested – in 1853, with America’s forced opening of Japan to trade and diplomacy on Western terms. Tōjō himself thought that the Opium Wars of the 19th century might be a reasonable point of departure.

And yet as Gary J. Bass points out in this magisterial account – long but never sprawling; thick with detail yet always engrossing – true victors’ justice, as far as some of the Allied leaders were concerned, would have involved putting Emperor Hirohito on trial and most likely hanging him. Large proportions of the Allies’ domestic populations wanted to see Japan destroyed. Bass reports that 85 per cent of Americans had been in favour of dropping the atomic bomb on Japan.

The judgments handed down in December 1948 were part of a much larger constellation of judgments made by the Allies right across the 1940s: about why Japanese politics and foreign policy took such a disastrous, aggressive turn in Asia; about what both they and the people of Japan wanted for their country after the war; and about the sorts of international standards – framed in terms of rights and crimes – they wished to apply across the postwar world.

To that end, it was soon recognised that executing the emperor was out of the question: it would render all but impossible the task of rebuilding Japan as a US-friendly democracy. Equally counterproductive would be an attempt to hold a wide range of Japanese legally accountable for the war. To an extent that Bass perhaps underestimates, under the American-led occupation there was an attempt to induce a sense of collective guilt among the Japanese – most notably in propagandistic radio broadcasts (about which hundreds of Japanese complained). Still, the dominant narrative, informing the trials and much of occupation-era policy, was that a handful of militarists had effectively captured Japan and had compelled everyone from the emperor downwards to go along with their aggression in Asia.

Bass’ account of the trials, informed by an impressive amount of archival work and interviews undertaken across the world by him and his researchers and translators, shows that to a significant degree this strategy worked. Japanese newspapers gave broad and generally favourable coverage to the trials, dissuaded from criticism both by the threat of Allied censorship and by what the Chinese judge Mei Ju-ao noted was a rather self-serving desire to limit war responsibility to the small ‘group of evil culprits’ standing in the dock. Bass includes a striking photograph of those ‘culprits’ sharing a bus from Sugamo prison to the court room: save for the American military police standing guard over them, they might be ordinary Tokyoites on the morning commute.

At the same time Bass reveals just how worried the Allies were behind the scenes about the conduct of the trials. When lawyers for the defendants questioned their legal basis, the judges struggled to respond, placing in doubt the legitimacy and credibility not just of the Tokyo trials but, by extension, the Nuremberg trials too. Bass shows judges and prosecutors reporting back to their home governments, some of them threatening to quit when proceedings appeared to deteriorate.

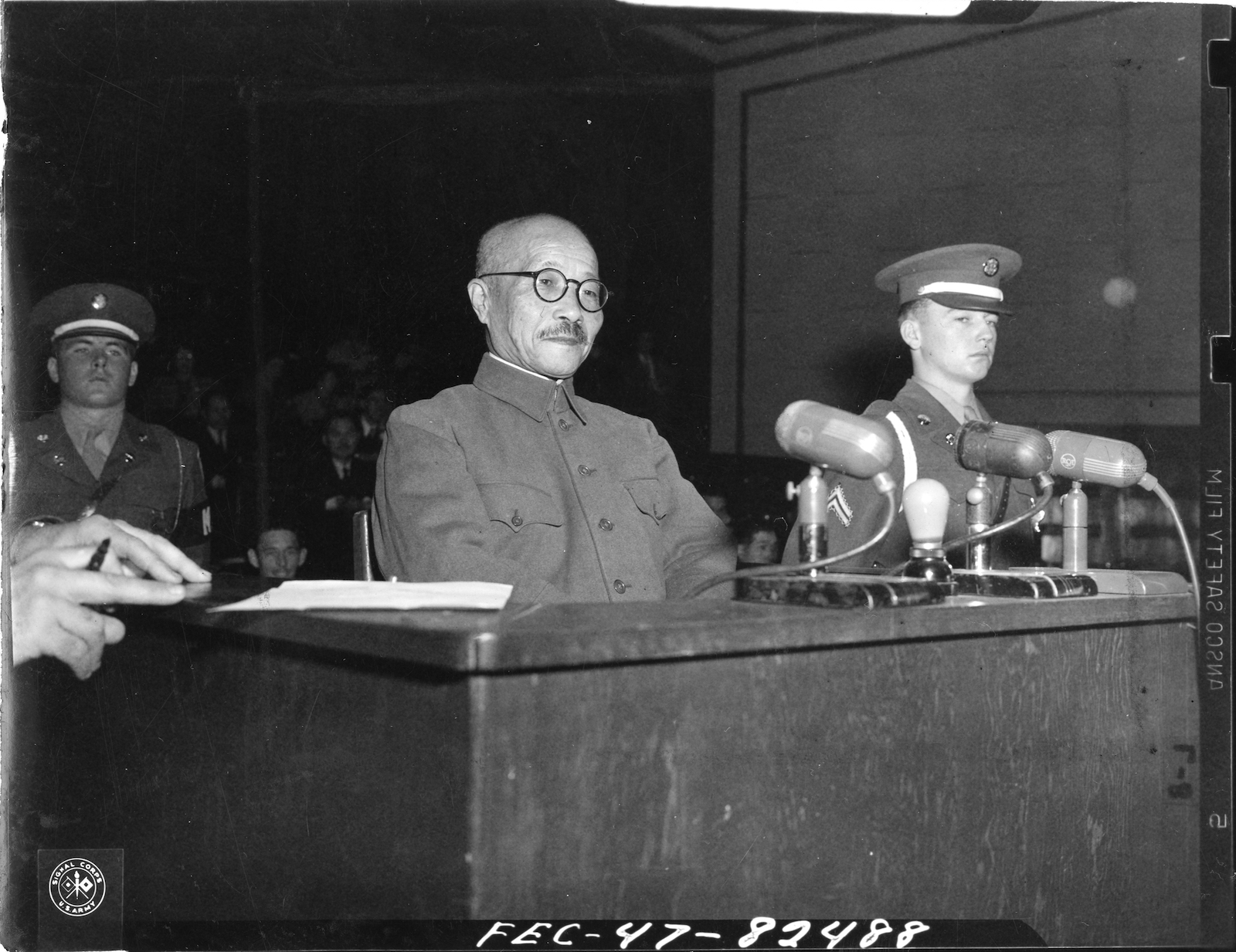

A memorable example of how the proceedings might go wrong was the cross-examination of Tōjō Hideki. An assistant prosecutor had spent a year studying Tōjō, only to be stood down at the very last moment by the comparatively unprepared chief prosecutor Joseph Keenan. The result was, writes Bass, ‘a debacle’. Tōjō was the one living under threat of the noose. But as a woman working in the British embassy was said to have put it: ‘Tōjō had a good morning hanging Keenan.’ He parried Keenan’s attacks, questioned his evidence and made the case that Japan had been acting in self-defence against encircling enemies – the US among them. (Nevertheless, Tōjō was hanged on 23 December 1948. Decades later, his soul was enshrined at Tokyo’s Yasukuni Shrine, along with other Class A war criminals, leading to diplomatic outcry in East Asia whenever a prominent Japanese politician pays a visit.)

Here, and elsewhere, Bass’ account is at once pacy – as befits a courtroom drama – and even-handed. He shows how the trials’ consideration of the events leading up to the war and then the war itself became, in effect, a first draft of a contested history: for those who believed Japan to be guilty of terrible crimes – Pearl Harbor; the Nanjing massacre; the brutal treatment of POWs – and for those who regarded Japan’s actions as forced upon it by Western imperialism.

The standout hero of the trials, for those inclined to the latter view, was the Indian judge Radhabinod Pal, whose views were informed by India’s experience of colonialism. In what Bass describes as a ‘monumental dissent’, Pal characterised the trials as ‘formalized vengeance’, denied that aggressive war-making had successfully been established as a crime under international law, and largely supported the self-defence argument. Pal went on to be fêted in Japan by those who felt that both the trials and the broader occupation were calculated to instil in ordinary Japanese a disabling sense of guilt – moral, if not legal. There is now a monument to Pal within the grounds of Tokyo’s Yasukuni Shrine, infamous across East Asia for its association with Japanese nationalism.

This reader would have liked to hear more about the legacy of the trials on postwar Japanese conservatism, and not just its ultranationalist strands (upon which Western commentators tend to focus). Nevertheless, this is a breathtakingly ambitious and well-executed piece of history, unlikely to be bettered as a portrait of the trials and their place in postwar global history.

-

Judgement at Tokyo: World War II on Trial and the Making of Modern Asia

Gary J. Bass

Chopper, 912pp, £30

Buy from bookshop.org (affiliate link)

Christopher Harding is a cultural historian and broadcaster based at the University of Edinburgh. His latest book is The Light of Asia: A History of Western Fascination with the East (Allen Lane, 2024) and he writes about Asia’s impact on Western life at IlluminAsia.org.