Experts have successfully reconstructed the face of a man who was a victim of Roman crucifixion, a discovery hailed as “almost unique” by Corinne Duhig, a bone specialist from Cambridge University.

The facial reconstruction was showcased on a BBC Four program, shedding light on the life of a man who met a harrowing end in a previously unknown Roman settlement. His skeleton was found in a burial site alongside others from the 3rd and 4th centuries.

“Seeing his face allows us to give more respect to him,” said Ms. Duhig.

The reconstruction was carried out by Professor Joe Mullins of George Mason University, Virginia, who described the project as “the most interesting” of his career.

Uncovering the Only Proof of Crucifixion in Roman England

The practice of crucifixion was one of the many “innovations” transported from Rome to Britain after the Roman Empire completed its conquest of the British Isles in the first century AD. This was firmly establishedafter archaeologists working in a small village in Cambridgeshire unearthed an ancient skeleton that contained clear and unmistakable signs of having been subjected to the cruel and barbaric punishment of crucifixion.

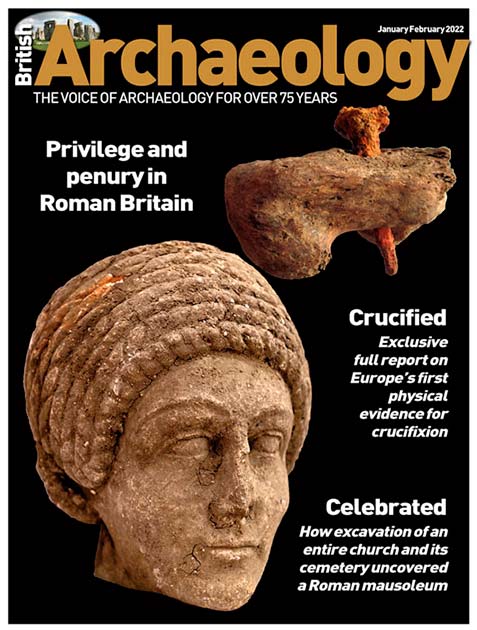

The discovery of the crucified skeleton was announced by British Archaeology Magazinebut the ancient remains were actually recovered during a 2017 excavation in the village of Fenstanton, Cambridgeshire, which is located 72 miles (116 kilometers) north of London.

The grave of the skeleton, which is the first evidence of crucifixion in Roman Britain, as it was found during digging at a future housing development in Cambridgeshire, England. (Albion Archaeology)

Roman-British Settlement, Cemeteries and Crucifixion

While digging at the site of a future housing development, archaeologists from the private company Albion Archaeology unearthed the remains of a previously unknown Roman-British settlement. Among other signs of occupation, the site produced five hidden cemeteries that contained the bodies of 40 adults and five children. Dating procedures proved the cemeteries had been in use during the third and fourth centuries AD, when Britain was under the control of the Roman Empire.

One of the excavated skeletons was of a man, estimated to have been between 25 and 35 years old at the time of his death, who’d apparently been a victim of violence shortly before taking his last breath.

This was not evident upon initial examination, but when the skeleton was being examined back in a laboratory in Bedford, technicians made the bone-chilling discovery. They detected a metal object embedded in one of the man’s heels, which was revealed to be a nail that had been pounded all the way through the bone.

The first evidence of Roman-British crucifixion has been found in Fenstanton, Cambridgeshire, England. The heel of a man found with an iron nail pounded through his heel bone was clear evidence of crucifixion. (Albion Archaeology)

Based on the nature and severity of this wound, the archaeologists knew the poor soul had been subjected to crucifixionfor crimes either real or imagined.

“The lucky combination of good preservation and the nail being left in the bone has allowed me to examine this almost unique example when so many thousands have been lost,” Cambridge University archaeologist Corinne Duhig, who carried out a thorough examination of the skeleton, told the BBC.

“This shows that the inhabitants of even this small settlement at the edge of the Empire could not avoid Rome’s most barbaric punishment.”

The victim’s face was reconstructed by US forensic artist Joe Mullins. (Impossible Factual/BBC)

Radiocarbon testing has revealed that the Fenstanton man lived sometime between the years 130 and 360 AD. The latter half of that dating period seems most likely to be accurate, since the cemeteries have been dated to that time.

In addition to the nail in his heel bone, the man’s leg bones showed other signs of damage, consistent with his having been chained or shackled. This would seem to offer proof that he’d been kept as a prisoner for a while before his final punishment was carried out.

Why Evidence of Ancient Crucifixion is So Rare

Even though crucifixion was a common Roman practice, skeletal proof of it is rare.

When someone was executed in this cruel and deliberate manner, their bodies were often tossed aside or buried in random locations, making them difficult for archaeologists to find. Roman crucifixion was a punishment reserved for rebellious slaves, political protesters, and the lower classes, none of whom would have been given much consideration by Roman authorities when it was time to get rid of their bodies.

Also, in many instances, victims of crucifixions were strung from wooden beams with rope, meaning no nails were required.

So just how rare are skeletal remains that show clear and unmistakable evidence of having been subjected to crucifixion during Roman times?

According to Corinne Duhig, only three other alleged examples had been reported worldwide at the time of the study on Fenstanton. These were unearthed in Larda in GavelloItaly, in Mendes in Egypt, and in a burial discovered at Giv'at ha-Mivtar in Jerusalem. Duhig believes the skeleton found in Jerusalem is the only one that can be identified with 100-percent certainty to have been subjected to crucifixion, since a nail was also detected in the heel bone of that unfortunate individual.

In most instances, it seems the Romans would remove the nails they used during a crucifixion before disposing of the body. But in the Fenstanton skeleton, the nail had been bent while being hammered in and had therefore become affixed to the bone.

“Burial practices are many and varied in the Roman period and evidence of ante- or post-mortem mutilation is occasionally seen, but never crucifixion,” commented archaeologist Kasia Gdaniec, a representative of the Cambridgeshire County Council’s historic environment team. “These cemeteries and the settlement that developed along the Roman road at Fenstanton are breaking new ground in archaeological research.”

The Fenstanton Roman-British cemeteries and the first evidence of crucifixion in the UK was so important that it made the cover of the prestigious British Archaeology magazine. (British Archaeology Magazine)

An Unknown Roman-British Settlement is Revealed

The news about the crucified skeletal remains has dominated the early discussion of the excavations at Fenstanton. But Albion Archaeology personnel have also recovered a number of items left behind by the people who occupied the Roman-British settlement found near the ancient cemeteries.

So far, the archaeologists have unearthed a horse-and-rider broach made from a copper alloy, various coins, pottery shards showing signs of artistic decoration, and the remains of cattle bones that had apparently been processed to make personal care items like soap or cosmetics. A large building and leveled surfaces used as courtyards or roads have also been excavated, offering evidence to suggest the Roman-British settlement featured advanced infrastructure.

Further excavations should provide more information about how people lived in this ancient unnamed Roman-British settlement. One thing already known is that those who strayed out of line in this ancient village could be sentenced to one of the most feared forms of execution ever developed: crucifixion!

Top image: Left; the reconstruction imae of Feb=nsatantion Man. Right; The first evidence of Roman-British crucifixion has been found in Fenstanton, Cambridgeshire, England. The heel of a man found with an iron nail pounded through his heel bone was clear evidence of crucifixion. Source: Left; Impossible Factual/BBCRight; Albion Archaeology

By Nathan Falde