Shiva, one of the principal deities in Hinduism, is a complex and multifaceted figure whose significance extends far beyond the bounds of religious worship. Revered as the god of destruction and transformation, Shiva plays a pivotal role in the intricate tapestry of Hindu mythology and spirituality. For those learning about this deity for the first time, there certainly is a lot to learn, especially with the great dimensions of Shiva’s character, his mythology, symbolism, iconography, and the profound impact he has had on Hindu philosophy and culture. So, let’s try and learn all that we can about one of the most important Hindu gods.

Shiva, the Auspicious One

Shiva’s roots are thought to be embedded in the prehistoric Indus Valley Civilization, where evidence of proto-Shiva symbols has been discovered. Over the millennia, the worship of Shiva evolved and found its place in the pantheon of Hindu deities. As such, it can be safely said that Shiva is one of the oldest gods in the world, and it has been actively worshiped for thousands of years.

Archaeological excavations in the Indus Valley, a cradle of ancient civilization that predates the Vedic period, have unveiled artifacts bearing symbols reminiscent of Shiva’s later iconography. The discovery of a seal depicting a proto-Shiva deity in a yogic posture, often identified as Pashupati, the lord of animals, provides a tantalizing glimpse into the ancient roots of Shiva worship. This archaeological evidence suggests that the worship of a divine figure with Shiva-like attributes may have existed in prehistoric times, further reinforcing the notion that Shiva’s origins are deeply embedded in the cultural and religious fabric of the Indian subcontinent. However, this interpretation is not universally accepted, and the connection between the figure in the seal and Shiva is still a subject of scholarly debate.

The Pashupati seal, showing a seated and possibly tricephalic (three faced) figure, surrounded by animals; circa 2350–2000 BC. (Public Domain)

Shiva in the Veda

Shiva’s origins are deeply entwined with the Vedic literature, the oldest sacred texts of Hinduism. While the Vedas primarily venerate deities associated with natural elements and cosmic forces, the Rigveda, the oldest of the Vedas, contains hymns that may hint at the nascent presence of a deity resembling Shiva. The Rudra hymns in the Rigveda describe a fierce and unpredictable god associated with storms, thunder, and the natural forces of destruction and renewal. Over time, these early depictions of Rudra would coalesce with other divine concepts to evolve into the multifaceted deity we now recognize as Shiva.

Evolution of Shiva’s Story

The Puranas, a genre of ancient Indian literature, play a crucial role in shaping the narrative of Shiva’s mythology. Texts like the Shiva Purana, Linga Purana, and others expound upon Shiva’s divine exploits, elucidating his role as the supreme deity and the cosmic dancer. The Puranic narratives weave together the diverse strands of ancient traditions, creating a cohesive tapestry of mythology that encompasses Shiva’s marriage to Parvati, his cosmic battles, and his benevolent manifestations. While the historical accuracy of these narratives is challenging to ascertain, they provide invaluable insights into the evolving religious landscape of ancient India.

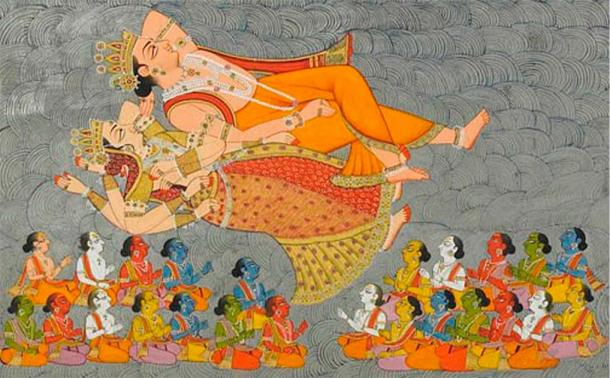

The Creation of the Cosmic Ocean and the Elements (detail), folio 3 from the Shiva Purana, c. 1828. (3rd paintings). The royal collection of the Mehrangarh Museum Trust, Jodhpur. (Public Domain)

The God from the Roots of Civilization

As Aryan and Dravidian cultures intermingled in the Indian subcontinent over the centuries, religious beliefs underwent a process of assimilation and syncretism. Shiva, in his various forms, became a unifying force, transcending regional and linguistic differences. The amalgamation of indigenous traditions with Vedic rituals led to the emergence of Shaivism as a prominent sect within Hinduism, with Shiva assuming a central role in the pantheon of deities. And, of course, with all the cultures contributing to the development of this god’s character, the mythology surrounding him only became richer and greater.

Shiva is often depicted as an ascetic, immersed in deep meditation atop Mount Kailash, the abode of the gods. In this state, he renounces the material world, symbolizing the transcendence of desires and attachments. His ascetic form embodies the essence of the yogic tradition, inspiring seekers on the path of spiritual awakening. The Ardhanarishvara, a unique aspect of Shiva, portrays him as half-male and half-female, conjoined with his consort Parvati. This union symbolizes the inseparable nature of the masculine and feminine energies, emphasizing the idea that creation arises from the harmonious interplay of opposing forces.

Shiva’s cosmic dance, known as the Tandava, is a key myth surrounding Shiva. This is a mesmerizing spectacle that symbolizes the eternal cycles of creation and destruction. In the Ananda Tandava (Dance of Bliss), Shiva dances with unbridled joy, portraying the dynamic interplay of the cosmic forces. The destructive aspect of the Tandava signifies the dissolution of the old, making way for regeneration and renewal.

One of the central myths in Shiva’s narrative is his marriage to Parvati. Parvati, an incarnation of the goddess Shakti, undergoes intense penance to win Shiva’s heart. Their union represents the cosmic balance of complementary forces, with Shiva as the still and unchanging principle (Purusha) and Parvati as the dynamic and creative energy (Prakriti). The divine marriage is a symbol of the unification of opposites, giving rise to the cosmic dance of life.

An equally important myth is The Churning of the Ocean (Samudra Manthan). During the churning of the cosmic ocean, various deities and demons collaborate to obtain the elixir of immortality (amrita). However, the churning also releases a deadly poison (halahala), threatening to engulf the universe. In a selfless act to save creation, Shiva consumes the poison, holding it in his throat. This episode underscores Shiva’s role as the benevolent savior, willing to endure suffering for the greater good of the cosmos.

The story of Ganesha, Shiva and Parvati’s son, is another compelling facet of Shiva’s mythology. When Shiva inadvertently beheads Ganesha, Parvati is grief-stricken. To console her, Shiva replaces Ganesha’s head with that of an elephant, symbolizing wisdom and the overcoming of obstacles. This myth also introduces the concept of Shiva’s third eye, which opened in a burst of fiery energy when he was angered, reducing the god of love, Kamadeva, to ashes.

Parvati: The Consort of Shiva

Parvati, an incarnation of the goddess Shakti, is a fundamental figure in Hindu mythology. She epitomizes strength, fertility, marital felicity, devotion, and power. Her role extends beyond that of Shiva’s consort – she is a deity of equal stature, embodying the active energy principle necessary for the universe’s existence and functioning. Parvati is often depicted as the mother goddess, nurturing yet fierce in protecting her children and devotees.

Parvati is expressed in many different aspects. As Annapurna she feeds, as Durga (shown here) she is ferocious. (Joydeep/CC BY SA 3.0)

In her relationship with Shiva, Parvati represents both the gentler aspects of Shiva’s nature and his counterpart in maintaining the balance of the universe. Her devotion to Shiva is a central theme in many stories, often highlighting her role in tempering his ascetic and destructive tendencies. The mythology surrounding Parvati’s pursuit of Shiva as a spouse, involving rigorous asceticism and devotion, is symbolic of the human quest for spiritual growth and enlightenment.

Shiva-Parvati Dynamic: A Cosmic Union

The union of Shiva and Parvati is emblematic of the union of consciousness and energy, the passive and active principles of the cosmos. They are often portrayed in a state of harmonious duality – Shiva as the formless consciousness (Purusha) and Parvati as the dynamic, creative energy (Prakriti). This union is not just a marital alliance but a cosmic one, representing the synthesis of opposites, essential for creation and life.

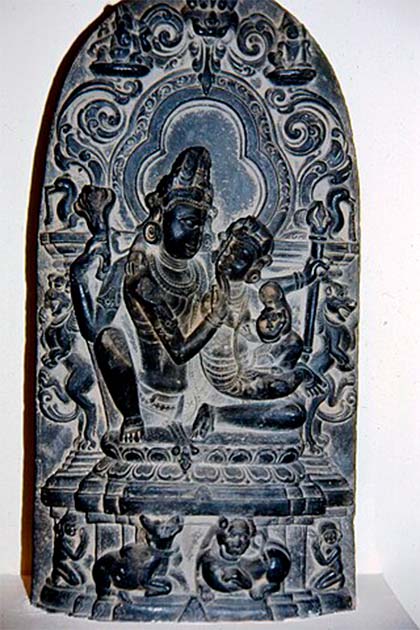

Sculpture of Shiva (left) and Parvati (right), at the Museum of Orissa, India. (Benjamin Preciado/CC BY-SA 3.0)

Offspring: Ganesha and Kartikeya

Shiva and Parvati have two sons, each significant in Hindu mythology: Ganesha and Kartikeya (also known as Murugan). Ganesha, the elephant-headed god, is revered as the remover of obstacles and the lord of beginnings. He holds a special place in Hindu worship, often invoked at the start of any venture for auspiciousness. The story of his creation and how he came to have an elephant’s head, involving both Shiva and Parvati, underscores themes of maternal love, filial duty, and the complex relationship between Shiva and his family.

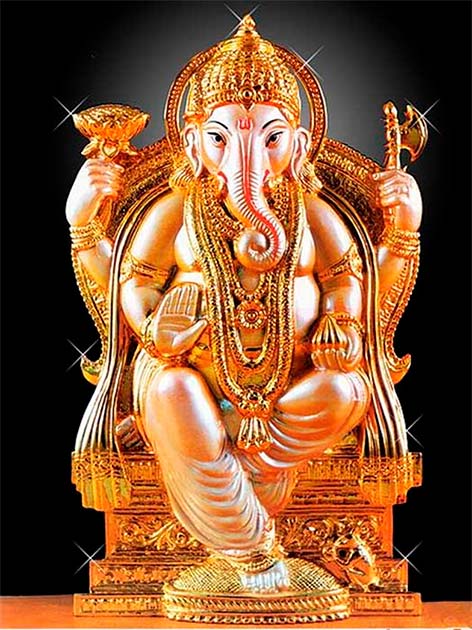

Statue of Ganesha (Sachinbatwal/CC BY-SA 4.0)

Kartikeya, the god of war, is a symbol of valor and youthful vigor. He is often depicted as a handsome and fierce warrior, leading the divine armies against demonic forces. In South India, particularly, Kartikeya is worshipped extensively and considered the epitome of beauty, bravery, and wisdom.

Kartikeya (also known as Murugan) seated on a peacock.(Claire H. /CC BY-SA 2.0)

Ardhanarishvara: Symbolic Unity

One of the most profound representations of Shiva and Parvati’s relationship is the Ardhanarishvara – an androgynous composite form of Shiva and Parvati, symbolizing the inseparable nature of masculine and feminine energies. This form conveys the message that the male and female principles are equally essential for the universe’s existence and balance. Ardhanarishvara is a powerful icon that speaks to the unity and equality of all genders and the interdependence of contrasting energies.

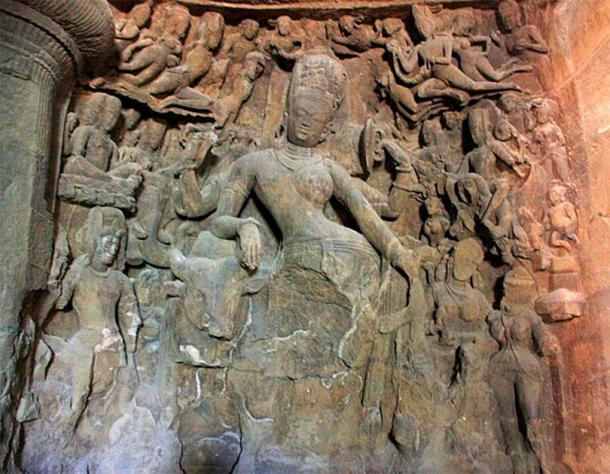

Ardhanarishvara (center): half female (Parvati) and half male (Shiva), feminine-masculine equivalence. (Ricardo Martins/CC BY 2.0)

Symbolism and Attributes Assigned to Shiva

Shiva, as the god of destruction and transformation, is adorned with a myriad of symbols and attributes, each laden with profound cosmic significance. At the center of Shiva’s forehead, the third eye, also known as the “eye of wisdom,” pierces through the veil of illusion (maya). Symbolizing inner perception and intuitive knowledge, the third eye represents Shiva’s ability to see beyond the apparent duality of the material world. It is a potent reminder of the importance of spiritual insight in transcending the limitations of the physical realm. Shiva’s disheveled hair, adorned with a crescent moon, is both a symbol of his ascetic lifestyle and a reservoir of divine energy. The flowing Ganges River, often depicted flowing from his hair, signifies purity, life, and spiritual purification. This dual symbolism underscores Shiva’s role as a source of both transcendent wisdom and life-giving force.

The crescent moon adorning Shiva’s head symbolizes the cyclical nature of time and the passage of lunar months. It also represents the calming influence of Shiva over the mind, reminding devotees to find serenity amid life’s tumultuous cycles. Additionally, the crescent moon is associated with Shiva’s benevolence, as he wears it as a result of rescuing the moon from the serpent Vasuki during the churning of the ocean (Samudra Manthan). A serpent coiled around Shiva’s neck serves as a powerful symbol of control over death and mortality. It also represents the kundalini energy, a potent spiritual force that, when awakened, leads to enlightenment. The snake’s presence signifies Shiva’s mastery over the primal forces of creation and destruction.

Wielding a trident, Shiva’s iconic weapon, symbolizes his dominion over the three fundamental aspects of existence: creation (Brahma), preservation (Vishnu), and destruction (Shiva). The trident embodies the eternal cycles of life, death, and rebirth, emphasizing Shiva’s role as the cosmic balancer and the agent of transformative change. The damaru, a small drum played by Shiva, symbolizes the primal sound of creation (Nada). Its rhythmic beat is believed to generate cosmic vibrations, shaping the fabric of reality. The damaru signifies the continuous dance of creation and destruction, illustrating the interconnectedness of all existence. Shiva also smears his body with ash, signifying the transient nature of material life. The ashes also represent the cremation ground, symbolizing the destruction of the ego and the impermanence of worldly attachments. Devotees apply ash to emulate Shiva’s renunciation and commitment to spiritual growth.

Meditating Shiva statue during Maha-Shivaratri festival. (Navneesh Ramessur/CC BY-SA 4.0)

The Pillar of Hindu Worship

Shiva is worshiped in various forms and avatars, each with its unique significance. As Nataraja, the Lord of the Dance, Shiva performs the cosmic dance (Tandava), symbolizing the eternal cycles of creation and destruction. The peaceful form of Shiva, known as Dakshinamurthy, is revered as the divine teacher who imparts spiritual wisdom to seekers. The Ardhanarishvara form of Shiva represents the androgynous unity of Shiva and Parvati, emphasizing the inseparable nature of male and female energies in the cosmos.

Devotees of Shiva, known as Shaivas, engage in various forms of worship, including prayer, meditation, and rituals. Maha Shivaratri, the Great Night of Shiva, is a significant festival celebrated by millions of Hindus worldwide. Devotees observe fasts, perform sacred rituals, and participate in night-long vigils to honor Shiva on this auspicious occasion. Shaivas often perform daily puja (worship) to Shiva in their homes or at temples. The ritual typically involves the offering of flowers, fruits, incense, and the lighting of lamps. Devotees recite prayers, chant sacred mantras, and meditate on Shiva’s divine attributes, fostering a personal connection with the deity.

The month of Shravan (July-August) likewise holds special significance in Shaivism. Devotees undertake austerities, such as fasting on Mondays, considered particularly auspicious for Shiva worship. The act of offering water (abhishek) to the Shiva Linga during this month symbolizes the descent of the holy river Ganges onto Shiva’s matted hair.

Mahadeva, the Great God

Shiva’s influence also extends beyond religious boundaries and has left an indelible mark on Hindu philosophy and culture. The concept of Shiva as both the destroyer and regenerator aligns with the Hindu belief in the cyclical nature of existence and the eternal cycle of birth, death, and rebirth (samsara). The philosophical school of Shaivism, dedicated to the worship of Shiva, has produced profound treatises exploring the nature of reality, consciousness, and the self. The arts, literature, and classical dance forms in India often draw inspiration from the stories and symbolism associated with Shiva. His portrayal in literature, such as the ancient Sanskrit epics and Puranas, has inspired poets, writers, and artists for centuries.

Shiva stands as a multifaceted and enigmatic figure in Hinduism, embodying the paradoxical forces of destruction and creation. His myths, symbols, and forms provide a rich tapestry for understanding the complexities of the cosmos and the profound philosophical concepts embedded in Hindu thought. From the ancient roots of the Vedas to the vibrant celebrations of Maha Shivaratri, the legacy of Shiva endures as a timeless source of inspiration and spiritual wisdom – not just for Hindus, but for all the people of the world.

Top image: Statue of Hindu God Shiva Nataraja in the cosmic dance. Source: Elena Kovaleva/Adobe Stock

References

Keay, J. 2000. India: A History. Grove Press.

Klostermaier, K. K. 2007. A Survey of Hinduism, 3rd Edition. State University of New York Press.

Rosen, S. and Schweig, G. M. 2006. Essential Hinduism. Greenwood Publishing Group.

Storl, W.D. 2004. Shiva: The Wild God of Power and Ecstasy. Simon and Schuster.