Strabo, a prominent Greek geographer, historian, and philosopher born around 64 BC, left an undeniable mark on ancient geography with his magnum opus, ” Geographica.” This monumental work, comprising 17 volumes, meticulously cataloged the geographical knowledge of the ancient world, offering us brilliant insights into diverse cultures, landscapes, and historical events. Strabo’s synthesis of earlier works combined with notes from his travels, and philosophical perspectives elevated him as a critical figure in our understanding of ancient geography. While some aspects of his accounts have faced scrutiny, no work is perfect, but Geographica remains a crucial source for comprehending the ancient world’s complexities.

Who Was Strabo?

Strabo was born in either 64 or 63 BC in Amaseia (Amasya in Cappadocia, Turkey). His family was rich and had been major players in the region’s politics since at least the time of King Mithridates V, around 100 years earlier. His mother was a descendant of Dorylaeus, one of Mithridates VI’s (also known as Mithridates the Great) most powerful commanders.

While several other family members had also served under the Great King, at some point towards the end of the Mithridatic Wars (conflicts between Rome and the Kingdom of Pontus) Strabo’s’ grandfather had switched sides and joined the Romans. It’s believed Strabo’s family was granted Roman citizenship as a reward. It’s also likely their changing of sides helped make the family particularly rich and powerful.

16th-century engraving of geographer Strabo. (Public Domain)

It doesn’t seem Strabo spent that much time in his hometown, possibly because his family wasn’t very popular with the locals after betraying the Kingdom of Pontus. He spent most of his life traveling and visiting Egypt and Kush and went as far west as Tuscany and as far south as Ethiopia. He also journeyed to Asia Minor and spent quite a lot of time in Rome.

He wasn’t alone. Travel throughout the regions he traveled was popular during this time, largely thanks to the peace offered by Augustus’s reign. Strabo lived in Rome from 44 BC to roughly 31 BC but in 29 BC traveled to Corinth to spend time near Augustus, who had settled there. Then around 17 BC he journeyed to Egypt and sailed up the Nile but didn’t travel again until 17 AD.

Strabo’s Studies

Strabo’s life wasn’t just marked by a love of travel, however. Before he began working on his Geographica and traveling the ancient world Strabo dedicated his life to the pursuit of knowledge and studied under several famous teachers. His studies began in Nysa (modern Sultanhisar, Turkey) where he was taught by Aristodemus. Aristodemus was a well-respected rhetorician who ran two schools of rhetoric and grammar, one in Nusa and one in Naples.

The school Strabo attended focused largely on Homeric literature and interpreting the Greek epics. Strabo loved Homer’s works and came to believe his poems held the secret to mapping Europe. Historians believe his time in Nysa either ignited his passion for the Homeric hymns or at the very least fanned the flames.

After finishing his studies under Aristodermus Strabo moved on to Rome at the age of 21. It’s this period of his studies that really highlights the caliber of tutors Strabo had access to. While there he studied philosophy under the Peripatetic Xenarchus, a respected tutor and adviser in Augustus’s court. Interestingly, while Xenarchus was Aristotelian Strabo differed from his master and was more of a Stoic.

While in Rome he also continued his grammar education, this time under Tyrannion of Amisus, one of Rome’s richest and most famous scholars. Tyrannion was also a traveler and a respected geographer which is significant considering who the young Strabo would become.

His most influential tutor however was Athenodorus Cananites. Athenodorus was a stoic philosopher who spent his life in Rome living among its elites and passed on these important contacts to the young Strabo. It was also he who is believed to have turned Strabo into a stoic and taught Strabo about parts of the Roman Empire he would never visit.

Athenodorus Cananites and the ghost, by Henry Justice. (Public Domain)

Strabo’s stoic beliefs may help explain his approach in writing the Geographica (which we’ll come to in a moment). Stoic principles advocate an understanding of the world through systematic observation and rationality, something that some scholars believe is evident in the way Strabo meticulously cataloged geographic details in Geographica. Also, Strabo’s emphasis on cause-and-effect relationships, systematic descriptions, and a rational approach align with Stoic ideals, potentially impacting his methodology in compiling geographical information.

The Geographica

Today Strabo is remembered for his masterpiece, the Geographica (Geography). The book is a massive encyclopedia of 17 books of ancient geographical knowledge written in Greek (reflecting Strabo’s’ Greek descent). These days around thirty manuscripts exist, the earliest of which is a fragment dating back to the fifth century AD. The next two oldest date back to 1397 AD and 1393 AD

Title page from Isaac Casaubon’s 1620 edition of Geographica. (Public Domain)

Much like the geography we’re taught in school today the Geographica covers two different types of geography- physical geography (like land masses) and human geography (politics, different cultures, etc.). While his work is his own, Strabo was heavily influenced by scholars who came before him, particularly the classical Greek astronomers like Eratosthenes and Hipparchus. This being said, while he made clever use of their work Strabo chose to take a different approach to them when writing the Geographica.

He laid this approach out in the first two books of the Geographica. Eratosthenes created his maps by combining astronomical data with coastal and road measurements. This was a good starting point, but Strabo felt this method was inaccurate. On the other hand, he didn’t have such qualms with the accuracy of Hipparchus’s work but felt it wasn’t descriptive enough.

Strabo recognized that his work was most likely to be used by powerful men who were more concerned with anthropology than numbers. He knew they already had access to information that told them where places were, and what they cared more about was the character of countries and regions.

So, Strabo took the work of the Greek astronomers and combined it with the work of men like Polybius and Posidonius. Polybius, (200 – 118 BC) was an ancient Greek historian born in Megalopolis, Arcadia whose work focused more on describing places and the people who lived there and analyzing the causes and effects of historical events. Posidonius (135 to 51 BC), meanwhile, was an ancient Greek polymath who wrote extensively on the physical and cultural aspects of the world, combining empirical observations with philosophical insights.

This all means that Strabo’s Geographica offers fascinating information on what the ancient world was like in his day. Alongside the above works (and more) Strabo used his own observations and traveled extensively. As he put it himself:

“Westward I have journeyed to the parts of Etruria opposite Sardinia; towards the south from the Euxine to the borders of Ethiopia; and perhaps not one of those who have written geographies has visited more places than I have between those limits.”

Strabo’s own experiences are most evident in books 11 to 14 which describe the Black Sea region, the Caucasus, Iran, and Asia Minor. His descriptions of the area are based on what he had seen but he deferred to ancient historians when covering the region’s history and the numerous wars fought there. In particular, he cited Demetrius in trying to make sense of Homer’s topography and the location of Troy. Likewise, book 17, which covers Egypt, the African shores of the Med and Mauretania is mostly based on Strabo’s journeys.

Map of the world according to Strabo. (Public Domain)

Writing a Masterpiece

When and where exactly Strabo wrote the Geographica is a topic of debate, but it would seem this labor of love took most of his adult life to write. We know that he spent much of his life traveling and repeatedly returned to both Rome and Alexandria where he spent a lot of time using their famous libraries for research purposes.

He first seems to have visited Rome around 44 BC when he would have been roughly 20 years old. At this point it’s doubtful he had begun his work and was there for education. During this initial visit, he studied under famous tutors such as Tyrannion, an educated Greek who had been captured by the Romans and forced to teach the likes of Roman statesman Cicero’s sons.

Strabo next visited Rome in 35 BC at 29 years old. At this point, his education should have been complete, so it seems likely that around then or shortly after he began working on the Geographica. It seems certain that his visit to Alexandria from 25-20 BC was spent making notes in its library and it was during this time he compiled his notes on his predecessors’ work that appear throughout the book.

The first edition was published in 7 BC, but the book went through several revisions over the years. The first edition covered the life of Augustus from 31 to 7 BC, but a later edition covered 6 BC- 14 AD. The last edition seems to have been published around 23 AD. This date can be derived from the latest event covered in the Geographica, the death of the Numidian king Juba II. Strabo would have been in his 80s when working on this final edition, highlighting just how long Strabo spent working on his magnum opus.

Statue of Strabo in his hometown (modern-day Amasya, Turkey). (Erturac/CC BY-SA 3.0)

Evaluating Strabo’s Work

While the Geographica was a revolutionary work, there are problems with it. Firstly, as with any historical source one must consider the issue of bias. Strabo was a Greek who spent much of his time in Rome (and whose family sided with the Romans), and it shows.

Historians have noted that Strabo tends to be particularly pro-Roman, often praising Roman ascendancy and how the Romans had spread over so much of the known world. At the same time, he was also very pro-Greek and often talked of Greek primacy over Rome in several ways. Rarely do the other cultures mentioned in the book ever live up to Strabo’s opinion of the Greeks and Romans.

The bigger problem with the work however is Strabo’s reliance on other sources, many of them quite old by the time Strabo was writing the Geographica. For example, despite living in Italy for much of his life, when covering it in the Geographica Strabo makes very few comments, relying mostly on his predecessors. This means much of the information he gives in certain parts of the book was already out of date, something he never makes the reader aware of.

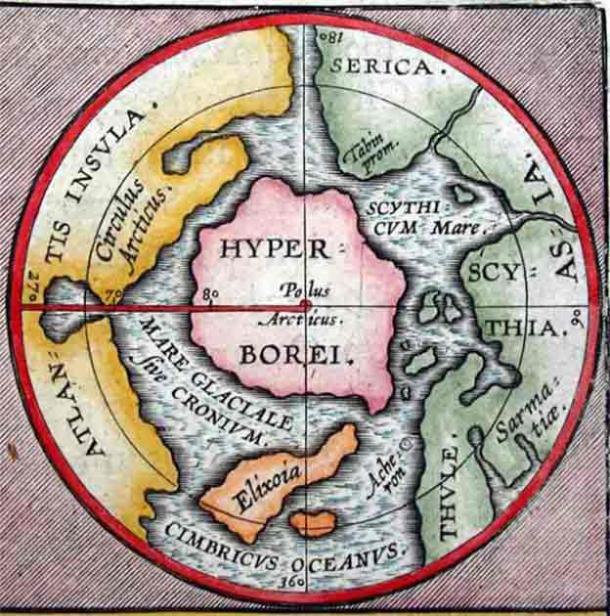

This overreliance on older sources led to certain inaccuracies creeping into the piece, especially when he covers places he never actually visited. He includes the mythical land of Hyperborea in Book II and uses it in the context of his geographical descriptions. Another example is in the section detailing India, where he tends to mix up the mythical with the real when describing its animals. His descriptions of mythical flying scorpions and gold-digging ants along the Ganges River, were taken from the works of earlier historians like Herodotus and Aristotle.

Ancient North Pole map of mythical lands including the central continent of Hyperborea. (Abraham Ortelius / Public domain)

Why the Problems Don’t Really Matter

The Geographica by Strabo is the only existing or surviving contemporary work that offers information about both Greek and Roman peoples and countries specifically during the reign of Augustus. As such it serves as a unique and valuable source that provides details about the geographical, cultural, and historical aspects of both Greek and Roman territories.

He may have over-relied on other sources at times, but the insights Strabo does offer are fascinating and he was particularly skilled at picking and choosing which information to include. The book is full of useful practical information. Things like the distances between cities, delineating borders between countries or provinces, and information on a region’s key agricultural and industrial pursuits.

The book is also full of background information on many of the places featured. Strabo liked to give the histories of the cities he covered, particularly how they were founded and the myths and legends relating to them. He often covered each region’s major events like the wars won and lost, how they had expanded or shrunk over time, and the celebrities who lived there. He was interested in the cultures of the places he described and covered their political statutes, ethnographic peculiarities, and religious practices.

He didn’t spend too much time reporting geological phenomena unless he found them particularly strange or interesting. For example, he was fascinated by the volcanic landscapes of southern Italy and Sicily as well as the rise and fall of the Nile waters and how the river flooded its banks each year.

The parts covering Greece, which fill three books are interesting reads for anyone interested in Homer. Strabo believed that Homer was a genius who had fully understood the geography of the Mediterranean long before anyone else and that his knowledge was hidden away in his poems. The right interpretation would reveal everything. Strabo spends the sections of the Geographica that cover Greece doing just this, trying to identify the places mentioned in Homer’s work and place them in the real world.

Conclusion

The importance of Strabo’s Geographica can’t be denied, it is a distinctive and indispensable exploration of the ancient world. Its significance lies not only in the scrupulous documentation of geographical minutiae but also in the nuanced amalgamation of empirical observations and the cultural tapestry of diverse regions.

Thanks to the Geographica countless scholars across the centuries have had access to a unique perspective on political structures, ethnographic peculiarities, and the interconnectedness of civilizations during the reign of Augustus. It’s a pivotal source, offering a comprehensive understanding of ancient geography that transcends mere cartography, delving into the profound human experiences within diverse landscapes.

Strabo dedicated his entire adult life to writing it. As far as we can tell, at best, he took a roughly eight-year break around 7 AD to focus on his travels. He worked on it well into his 80s and is thought to have died shortly after the final version was published. That kind of dedication is impressive, no wonder it produced such a historically important masterpiece.

Top image: 1700, Cellarius Map of Asia, Europe and Africa according to Strabo. (Right) Drawing of Strabo. Source: PicturePast/Adobe Stock, Public Domain